Är det en ny era? Min personliga åsikt är att så inte är fallet. Dock är förmodligen denna uppgång i tillgångspriser avvikande från historiken då delvis marknadskrafter satts ur spel. Centralbankernas interventioner (verbalt eller med handling) har delvis satt marknadskrafterna ur spel med resultatet att banker, stater och bolag som skulle gått i "konkurs" "överlevt".

Centralbankernas vansinniga policy att skapa tillväxt genom att blåsa upp tillgångspriserna tycks ha lyckats, men till vilket pris?

Ovanstående mening är inget konspiratorisk uttalande. Bernanke ansåg själv att "higher stock prices" var ett möjligt "stimulansområde" för tillgångsköpen 2010. Uppåtgående tillgångspriser ansåg önskvärt då och anses förmodligen även önskvärt nu:

(...) And higher stock prices will boost consumer wealth and help increase confidence, which can also spur spending. Increased spending will lead to higher incomes and profits that, in a virtuous circle, will further support economic expansion." (Ben Bernanke november 4, 2010, inlägg finnes här).

Resultatet av denna policy, som först Bernanke implementera, är att centralbankerna idag äger drygt 33% av den globala obligationsmarknaden

http://www.zerohedge.com/news/2017-06-04/central-banks-now-own-third-entire-54-trillion-global-bond-market

Uppenbarligen har detta "fungerat", men jag förblir skeptisk på grund av nedanstående anledning:

"If economics were a hard science like chemistry, you’d mix a little of this with a bit of that and the concoction would lead to strong economic growth, full employment, rising home prices, buoyant financial markets, and low inflation every time. But economics is a soft science, and real life simply doesn’t work so predictably. Though economists might wish otherwise, economics is, at its core, behavioral. Modern economies are too complex to be reliably modeled; their connections and correlations are lose and imprecise, the second- and third-order effects largely immeasurable the fickle vagaries of individual and aggregate human behavior utterly unknowable. Put an economist in a powerful government job and provide levers that can be pulled to start the printing presses, set reserve requirements, fiddle with the Fed funds rate, expand the Fed’s balance sheet, and deliver indecipherable communiqués, and that economist will feel compelled to pull those levers. He or she, like a monkey with a typewriter, might even give us Shakespeare (or Adam Smith) on occasion. But mostly that economist will spout gibberish, a mélange of untested and potentially counterproductive measures that unleash all manner of unintended consequences." (Seth Klarman, 2012 letter)

Även om allt ser ut att gå vägen för centralbankerna så gömmer sig skit under ytan. Kolla bara 2 minuter på nedanstående video om subprime marknaden i USA. Subprime marknaden har börjat löpa amok igen, fast denna gången är det billån.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4U2eDJnwz_s&t=12m16s

Mina tankar bör dock vara irrelevant för er läsare, utan istället kommer två erkända investerares tankar nedan (Maida och Grantham). En av dessa tror på en form av ny era och en tror på en bubbla:

Vito Maida

"“This too shall pass.” Valuation seems to have been forgotten in the investment process. This has been evident over the past several years but we are now in the territory of “reckless abandon” as “animal spirits” take over. There are several reasons for the current state of affairs. Among them:

• Persistent record low interest rates fuelled by Central Bankers fearful of a decline in asset prices;

• Enormous corporate share repurchases funded by ever increasing levels of debt;

• The large amount of fund flows into passive investment strategies that are fully invested and by definition must continuously purchase equities in an ever rising market begetting higher and higher prices.

These factors coupled with investor optimism have pushed current equity valuations to record highs. In our view risk is now exceptionally high; particularly relative to potential future returns. While we can’t predict how long these markets will persist, history tells us market sentiment often changes quickly and for unforeseen reasons. Below we list some of the risks that are being ignored:

• Political risk, with President Trump being embroiled in several investigations that threaten his administration’s pro-business policies;

• Geopolitical risks, especially in the Middle East and the Korean Peninsula;

• Higher interest rates being telegraphed by the U.S. Federal Reserve;

• Valuations that sit near all-time highs.

The current environment is eerily similar to previous peaks in 1987, 2000 and 2007. In each of those circumstances valuations were ignored. Investment pundits of all stripes provided eloquent justifications for continued optimism and ever rising prices. Investors got enamoured with the popular investment of the day and impatient with any asset that didn’t show an immediate return. Any rational argument rooted in financial and historical norms was dismissed in favour of the new paradigm of the day. "(Vito Maida Q1 2017)

Jeremy Grantham

In recent weeks, as US equities have hit new all-time highs, one of the world’s most high-profile perma-bears, Jeremy Grantham of the Boston investment firm GMO has declared that we may have entered a new era of sustained higher stock market valuations and that we are not in the “bubble” that many have been so eager to call.

Mr Grantham argues that this time really might be different because the higher earnings power of an ever more consolidated number of US companies justifiably mean that these mega-corporations deserve to trade at higher multiples than in the past. Such views are highly unfashionable in an age of deeply-held cynicism about the role of central banks supporting asset prices and lingering trauma from the crash of 2008. (https://www.ft.com/content/be7aad0e-4abe-11e7-a3f4-c742b9791d43?mhq5j=e3)

Från GMOs kvartalsbrev sida 9-16 så kan man läsa Granthams senaste tankar i detalj och de är fascinerande:

"Oh, the good old days!

When I started following the market in 1965 I could look back at what we might call the Ben Graham training period of 1935-1965. He noticed financial relationships and came to the conclusion that for patient investors the important ratios always went back to their old trends. He unsurprisingly preferred larger safety margins to smaller ones and, most importantly, more assets per dollar of stock price to fewer because he believed margins would tend to mean revert and make underperforming assets more valuable.

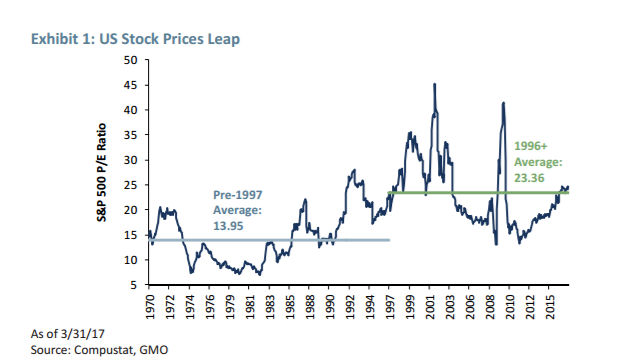

(...)Exhibit 1 shows what happened to the average P/E ratio of the S&P 500 after 1996. For a long and painful 20 years – for someone betting on a steady, unchanging world order – the P/E ratio stayed high by 1935-1995 standards. It still oscillated the same as before, but was now around a much higher mean, 65% to 70% higher! This is not a trivial difference to investors, and 20 years is long enough to test the apocryphal but suitable Keynesian quote that the market can stay irrational longer than the investor can stay solvent.

The behavior of the S&P 500 in 2002 might have been whispering in my ear, but surely this is now a shout? The market has been acting as if it is oscillating normally enough but around a much higher average P/E.

Grantham menar att skiftet uppåt värderingsmässigt åstadkommits av att företagen lyckas bibehålla högre marginaler än tidigare. I de 2 nedanstående graferna illustreras hur marginalerna för de amerikanska företagen förhållit sig historiskt.

(...) We value investors have bored momentum investors for decades by trotting out the axiom that the four most dangerous words are, “This time is different.”2 For 2017 I would like, however, to add to this warning: Conversely, it can be very dangerous indeed to assume that things are never different.

Of all these many differences, the most important for understanding the stock market is, in my opinion, the much higher level of corporate profits. With higher margins, of course the market is going to sell at higher prices.3 So how permanent are these higher margins? I used to call profit margins the most dependably mean-reverting series in finance. And they were through 1997. So why did they stop mean reverting around the old trend? Or alternatively, why did they appear to jump to a much higher trend level of profits? It is unreasonable to expect to return to the old price trends – however measured – as long as profits stay at these higher levels.

(...) ■ The single largest input to higher margins, though, is likely to be the existence of much lower real interest rates since 1997 combined with higher leverage. Pre-1997 real rates averaged 200 bps higher than now and leverage was 25% lower. At the old average rate and leverage, profit margins on the S&P 500 would drop back 80% of the way to their previous much lower pre-1997 average, leaving them a mere 6% higher. (Turning up the rate dial just another 0.5% with a further modest reduction in leverage would push them to complete the round trip back to the old normal.)

This neat outcome tempted me to say, “well that’s it then, these new higher margins are simply and exclusively the outcome of lower rates and higher leverage,” leaving only the remaining 20% of increased margins to be explained by our almost embarrassingly large number of other very plausible reasons for higher margins such as monopoly and increased corporate power. But then I realized that there is a conundrum: In a world of reasonable competitiveness, higher margins from long-term lower rates should have been competed away. (Corporate risk had not materially changed, for interest coverage was unchanged and rate volatility was fine.) But they were not, and I believe it was precisely these other factors – increased monopoly, political, and brand power – that had created this new stickiness in profits that allowed these new higher margin levels to be sustained for so long.

(...)Perhaps the best bet for higher rate equilibrium in the next few years is a change in the dominant central bank policy of using low rates to stimulate asset prices (which they clearly do) and stimulate growth (which, other than pushing growth back or forward a quarter or so, I believe they do not do). With 20 years of Fed support for this approach and loyal adherents in the ECB and The Banks of England and Japan, changing the policy is unlikely to be quick or easy. It is a deeply entrenched establishment view, or so it seems. President Trump is admittedly a very, very wild card in this game, and he said a few anti-Fed things in the election phase, for whatever that is worth. He also gets to appoint five new members, including the chair, in the next 18 months. But in the end, will a real estate developer with plenty of assets and an apparent interest in being very rich really promote a materially higher-yield policy at the Fed? Possible, but quite improbable, I think.

(...)What this argument probably does mean is that if you are expecting a quick or explosive market decline in the S&P 500 that will return us to pre-1997 ratios (perhaps because that is the kind of thing that happened in the past), then you should at least be prepared to be frustrated for some considerable further time: until you can feel the process of the real interest rate structure moving back up toward its old level

(...) In conclusion, there are two important things to carry in your mind: First, the market now and in the past acts as if it believes the current higher levels of profitability are permanent; and second, a regular bear market of 15% to 20% can always occur for any one of many reasons. What I am interested in here is quite different: a more or less permanent move back to, or at least close to, the pre-1997 trends of profitability, interest rates, and pricing. And for that it seems likely that we will have a longer wait than any value manager would like (including me). "

https://www.gmo.com/docs/default-source/public-commentary/gmo-quarterly-letter.pdf?sfvrsn=44